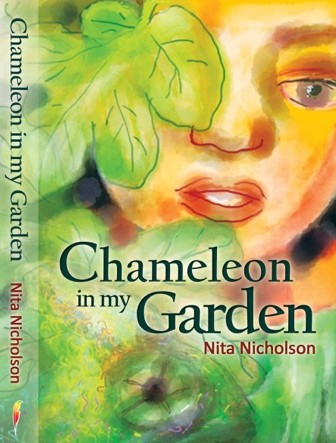

After finishing my first novel, Chameleon in My Garden, I wanted to savour more of the place to which the story belonged. I had fought a campaign for my husband’s release from prison, but, having won the disfavour of the Libyan regime, I could not return to join him when he was freed. Libya itself was still a prison for him as for everyone.

Those who might have told me more about the history of this land which had so absorbed me had sadly passed away. I regretted being so preoccupied with my own challenges that I had not found time to ask them about their stories. I forgot about the importance of their memories.

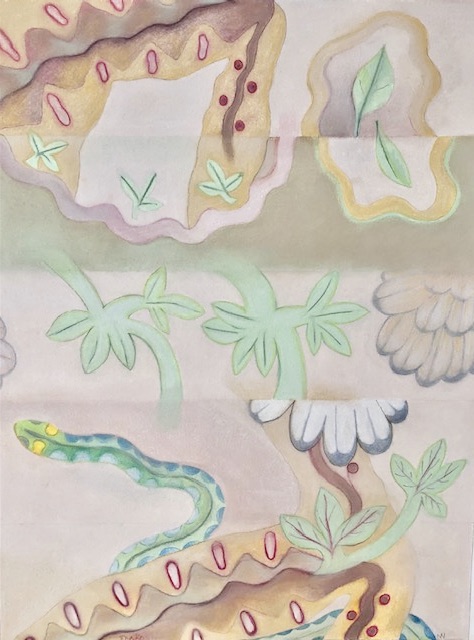

Having spent thirty years writing ‘Chameleon’, and needing to return to writing, now on my laptop, I reflected on what could possibly follow my husband’s release. That story has yet to be concluded. It was interrupted by the Arab Spring with its searing elation and soon-to-be dismay. It is a story more suitably told by present and future Libyan generations. But writers cannot resist a story. Now that I knew that what came after ‘Chameleon’ could not have form until I had fathomed what had gone before, I turned to the possible memories. This became my second novel, This Land Belongs.

I started with the date of 1922, the year my female protagonist, Fathia, was to be born. There were few clues or intimations that I could latch onto. There was a grandfather much beloved and spoken of with pride. He was the Mufti of Derna imprisoned by the Italian colonial authorities some years later, whose photograph I had seen displayed in the now replaced British Museum Library. There was Derna, a place I had visited several times, a town that was blessed with water that flowed from a spring. It lay on the North African coast of the Mediterranean. And, of course, there was Benito Mussolini who was preparing to march on Rome, just as Fatma was ready to be born in Derna, delivered by a Sicilian midwife from the convent.

These fragments of a story were sufficient to engage me in a search for more. They took me further back in time to 1911 and the Italo-Turkish war of 1911-1912, precursor of WW1. The stage was set for a full cast of characters to emerge of their own logical accord. There was the history teacher vexed with a dilemma. Then there was the farmer and his valley farm in Shahhat in the Green Mountains, and my memory of a sweet dessert of walnuts and pomegranates. Also, there came the eager foreign journalists, investigators of an international incident surrounding the murder of an American, and witnesses to a brutal invasion, drinking coffee in the cafes and struggling with their representations of the truth. Along with the Sicilian midwife came her brother, injured in WW1 and keeper of Sicilian bees. Next a laicised priest with a camera, and Sicilian geographers with ambitions for adventure and fame.

I did not create a staged play of good and evil actors but found there were many Italian actors whose generosity and basic goodness redeemed the Italian spirit of the time. Movingly, Moslem converts, English, Jewish and Catholic, were prepared to throw their lot in with the heroic Senussi resistance.

Backbone to the Derna community was a collection of aunts, mothers and daughters who nurtured their families throughout thirty years of oppression and war of one kind or another. I paid tribute to them. In the process of getting to know them, they became part of my own real family. On the laptop page, as in life, these people were populating my imagination, and they stood shoulders above their notorious oppressors, those with such illustrious or intimidating names, such as Italo Balbo the Ras of Ferrara, Rodolfo Graziani the Butcher of Fezzan, and Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini, Il Duce.

Encompassing all this humanity was the alluring landscape arena of Cyrenaica, almost mythical in its scope for allowing a story to unfold. The Green Mountains, the Ancient Greek site of Cyrene on the hill slopes overlooking a fertile plain up to the Crescent Bay of the blue Mediterranean.The massive desert hinterland, unknown and unmapped, was a mystery. The orchards of Derna, unforgettable for the overhanging abundance of fruit trees in bright sunny lanes, and the white domes of its mosques. There were oases with date-palm trees, oak, carob and juniper forests on the plateau, hillsides perfect for picnics on a carpet of wild flowers, horse treks in the mountains, the long ceremony of tea-making and sweet pastries, sumptuous weddings and glittering brides, births and tragic deaths. However, most alarmingly, there were the wastelands commandeered by the Italian colonialists for concentrations camps.

Along with the collision of these clashing realities came a sense of everything being super-charged with energy, light, and the human capacity for charity. But also, alarmingly, with the human capacity for vanity and its corollary of inhumanity.

Coming to the final chapters, I understood I had revealed to myself a beautiful landscape that had been purloined and oppressed by a colonial occupation for thirty years or more. It was a usurpation of power and agency that destroyed the natural continuity of life in the very land that was stolen. It had disrupted ancient trade patterns and normal communing between local and diverse communities. It had deprived a people of their own unique destiny. What a terrible fate it was, to be located at the north of one continent that faced the southern shore of another, and there to lie under an alien gaze that might be loaded with either a hateful antipathy or an envious desire.

So the final chapters give the floor to the actors’ and the poets’ voices. With new independence, a sense of belonging to the land and of the land belonging was rightfully returned, once fascism in Europe was defeated, after a phenomenal struggle in which so many lives were lost.

New research on the plight of Libyan Jews under Italian persecution was brought to my attention, and I realised there was an additional searing memory which I had not included in the first edition of This Land Belongs. There were natural links already embedded in the early part of the story, and so it was natural that a second addition was written to include extra chapters in final Part 10.

I see Libya as a living organism. It is also a carpet, a pathway, a journey within and across, a longing and an inconvenient convenience, still longed for, still enviously desired.

Paperback available November 2023. Download Kindle App to read on ANY DEVICE — Click here.

All proceeds from sales (less publishing costs) are donated to Médecins Sans Frontières (UK) (Doctors Without Boarders) supporting flood victims in Derna, Libya.

(new novel, fourth, in progress, working title)

Chapter Three

Chiaroscuro

It was the visiting hour in Ward 23. The visitors were talking softly. To patient Marwan, the hubbub of their conversations was calming. He rarely had visitors himself and there were none for him that day. At such times, he liked to keep busy with his pencil.

There was no one for the new patient opposite who had arrived in the afternoon and was presently sitting on his chair beside his bed. He sat still posing himself like a perfect model. He was middle-aged with greying hair and looked reminiscent of someone, maybe the famous Egyptian film star who went to Hollywood, Omar Sherif. He had the same refined features and would have turned heads in better times. Patient Marwan imagined sunlight rippling over his face, his eyes smiling and a show of perfect, white teeth. Perhaps he was still a head-turner.

But that was not how he looked now, not when all the life in him had gone. Patient Marwan drew him in rough outline and shaded him in silhouette. The hollows round his eyes were etched feint in grey chiaroscuro. It was a sketch of soft cross-hatchings, smoothed with the rubbing of his finger, He would refine it later. It could have been a self-portrait, of himself as an effigy of restive stillness, running on empty, staring but not seeing. Except that Marwan saw everything.

The film star lookalike had been frozen in his pose for almost half an hour. It looked stressful to sit that way, so rigidly straight-backed. Patient Marwan used the visiting time remaining to trace the wisps of hair that half-framed his sitter’s head, the arch of his eyebrows turning grey just suggested, his eye sockets which added depth, the cheek bones which caught the light and the sagging jowls which joined the folds of his neck. He had treated him gently, kindly, searching for the soul within that had vacated its devastated body. He paused and saw that, contrary to the dreamy image he had imagined, he had drawn the new patient both with the probing of a mystic and the precise incision of a surgeon’s knife. His sketch revealed more than his eyes could have seen, something bedded deeper than the surface stillness. Patient Marwan the artist was pleased with that, and, at the same time, he was concerned about the mental state of the unwitting sitter whose stasis he had taken advantage of. Could the new patient be meditating?

It was in the few remaining minutes of the hour, when Marwan was folding his notebook closed that the answer came. The new patient flung his blanket and pillow across his bed, upsetting his tray, plastic water-jug and pills sent flying. Oblivious to the clutter around him, he then stood by his upturned chair, flung his arms wide, and delivered a blistering rant that ruptured the sedated quiet of the psychiatric ward.

It didn’t help that his guttural shout was unintelligible. It sounded like a threat. It was a rupture like the breaking of plate glass – a cry born out of nothing intelligible to those who did not know him. Patient Marwan recognised the shout as a cry of distress.

A coin had been thrown along with the pillow. It had rolled under the patient’s bed and went on rolling. Patient Marwan listened to it spinning until it fell flat with a tiny clink.

By five minutes to eight, all visitors had been ushered out. A doctor was called and the new patient, whom they called Ismael, was sedated. At five past, he was safety tucked in bed, and the day nurse Aisha was preoccupied with recording the incident.

Patient Marwan felt uneasy. He told the nurse he thought a conversation would have been better, a few moments of listening to the man, a few words of comfort. For him, words were everything; but just now he couldn’t find the right ones to describe what he had seen. He, the self-styled wordsmith, was searching for the right word. Some feelings just don’t have words to match them.

“You will not be aware, my dear,” the day nurse Aisha advised him when she found a minute to spare. “But he’s been transferred from the cancer ward. It all happened without a moment’s notice. But he will settle now.”

So the matter was dealt with, it seemed. The ward was quiet again. The disruption was smoothed over. Perhaps it was considered best forgotten, and must therefore be exiled to the amnesia of a long night’s lack of sleep. Before consigning his pad and pencil to his locker, patient Marwan drew a faint outline of the distraught new patient in a style more suited to a cartoon, the face possessed by a scream. Not original he knew. It had been done before by someone much more talented, but it said some of what he wanted to say. There remained the more that was crucial, which, like the word, eluded him. He did not expect to sleep well.

Notebook 7 The curve of time

Chapter 14

Curves

For Selma, the chance meeting with Frank or Frankie on that inauspicious day of cloud and threatened rain was special. She did not have the word to pin it down. Portentous maybe. It was the feeling of the universe nudging her. She had been about to leave, he had mistakenly thought he had missed an assignation, but a stale cupcake had made a connection between them.

Then there had been the library, the noticeboard, the bird charm on the bracelet. Perhaps it was no surprise, then, that the name Ben Falcon came to mind. Was it Falcon? Had she imagined Falcon on that little piece of card which he had left on her desk, dampened by the blush of petals and crushed in her pocket beneath the flowers, attached like a little tag, a memento, a reminder? Somehow these improbable connections had contrived to form a chain: peregrine falcon, Falcon. She was curious.

She found the tag and send an email to the address on the card. Her message was brief and casual, the subject In search of peregrines. The message: Making connections with birds, mainly of the peregrine falcon kind, and thought of you. Using my camera loads. Hope you are well and doing fine at the office. Selma

Ben, that is the Ben of ben@falcon.com, had found the message from Selma in his Junk Mail some few days later. The subject had struck him as odd, in search of peregrines. He would not have found it but for the fact that he had mislaid an email from a friend some weeks back, Mike, asking him to meet up. So he was searching in Junk Mail. It was another of Mike’s hare-brained plans, typical of him, always one to disappear over the horizon in search of unicorns. This time it was something about sticking a pin in a map to find a place from which to explore the proverbial end of the rainbow. Mike was always travelling somewhere. However, while still employed, Ben had dismissed the proposal. Then later, since he had resigned, he found himself at a loose end – maybe Mike’s email had some worth to it. And there it was, with Selma’s email right below it.

The juxtaposition had seemed serendipitous. It was one of those non-coincidental occurrences that are known to some, in particular to Ben, as synchronicity. Ben was always looking for messages delivered in mysterious ways. He was surprised. Selma had shown no inclination to respond to his approach when she had left the firm. Faint-hearted and all that, he had failed to ask for hers in return. Now he had every reason to follow through.

He would take his time. He would do it tomorrow, or the day after, not to look too eager. But then he noticed the email was dated two weeks previous.

Amazing to hear from you. Glad to see you are using your camera. Of course I see how you made the connection Peregrine – Falcon. It’s a medieval nickname for a pilgrim. You can call me ‘Pilgrim’ if you like.

So then he suggested coming North to see her, since he was unemployed and at a loose end. He would do some research on peregrine falcons himself in the meantime.

Various sources gave Ben different interpretations of the name Falcon. He knew about them, of course he did, always researching the derivations of things. The falcon was a spirit animal, its meaning at essence . … signifying wisdom, vision, and protection. He liked the idea of a beautiful creature being powerful and protective. It seemed to invite him to seize something visionary. It seemed to show the way. Who had named him Falcon, he wondered, because he had been fostered many times. He had lost count of how many.

Ben found solace in searching for the details others missed. He seemed to live in a world of his own. He discovered the word ‘falcon’ was derived from 13th-century faucon, itself derived from Old French of the same spelling. It could even be that this in turn was derived from the Late Latin falconem, which drew its root from falx, meaning curved blade, as of a weapon. He loved the way the meanings unfolded, tracing a path through time., like a fractal. He was sure curved blade referred to the sweep of its swings, but the peregrine falcon also had sharp curved talons and a curved beak. Everything about the peregrine falcon is curves. It even hunts in a curve. When it stoops from a height to hunt its prey, it turns its head for speed avoiding the drag of a direct approach.

Chapter 7

Night thoughts

It was late. Sarah heard a scratching on the window. She checked the front of the house where the holly tree was shaking in a breeze. The driveway was clear and the street empty. She checked at the gate and there was no sleek saloon parked in the road. She reminded herself that the phone never rang. No one knew her number. The postman delivered only flyers.

Lying with her pillow alongside her, she reassured herself there was no reason to fear being followed. Not any more. It was she who did the following now, treading a circuit of tested routes that always returned her home. Yet they had not forgotten her altogether. A voucher was always waiting for her at the Post Office. How they had cowed her, kept her low. And who were they to do that to her, when they had no visible reality? Had she turned herself into stone? Made herself unmovable.

These days, little reminders of the past came to her piecemeal. They were assembled as an inventory of incidents and places, maybe all imagined. Disordered and dissonant they resisted coherence. They place-shifted as each new retrieval challenged the previous mosaic. Sometimes Arabic intruded, words like aib , inshallah, mabruk fi yithn alla,, uskuti, ya mama, mughrab, nazik, salaam, selamideiki, – forbidden, God willing, congratulations, in the gift of God, be quiet, oh mother, dusk, nice, peace, bless your hands. They echoed in her head like the bleating of a ewe in a distant valley, a mother calling for her lost offspring.

She had not forgotten the oasis on the Jeffara Plain. There was the sound of hands patting bread flat to the wall of an earthen oven, the touch of a hand painting a filigree pattern with henna on her foot, and often the muezzin’s call to prayer. There were special places like a sunken garden. How cool it had been in the step down even though the day had been hot and humid. She remembered a liaison with someone in a library. Or was it a hotel? Then being followed by a car; the purring of its engine, she remembered it was green, kerb-crawling. If it was not a car that followed her, then it was a man on foot wearing a large brimmed hat, and not a Libyan. There were other scenes, too painful to be to be thought of as real, as when the lights went out and his hand, someone’s hand, someone special, dropped his cigarette. There was the child lying ill, hot and terrified and would not be touched or comforted; and the boy who had come home breathless with running so fast. Then there was the last intrusion of sound that moved like a shiver down her back, literally down her back, and the roar of a cavalcade. Every night, her last thoughts before she fell asleep were of a child who needed to be comforted and a boy racing home.

She always woke before daylight. Perhaps it was the screech of an owl that disturbed her. Perhaps the yowling of a cat. She shifted the incline of her neck to the pillow to find the best lay of her spine, achingly aware of the skew of its curve. Every turn of her shoulders to the left or of her legs to the right reminded her of the trauma which had severed her present self from her real self and angled her awry from what she had been in every sense of the meaning of ‘awry’.

Lying askew, she felt the pain melt into the mattress. She reflected on the mystery of the pieces gathering into a narrative of sorts. The fabric of her past life was mending itself and even though the emerging story was not sufficiently coherent to share, she was pleased to find some linkages forming.

At daylight, an arrowhead of starlings performed its drama above the poplars. The murmuration was deafening. Only when they moved on to perform in another tract of sky, could she hear the wind in the poplars as a calming hush.

Notes: A boy, a girl, my children, the accident. Who was it dropped the cigarette? The same perhaps who told me to hold on? Glissando is the word I’m looking for – the wind brushing the trees. Playing the leaves like a bow on the strings of a violin.

Hood

I fell headlong onto the back seat. They tied my hands behind my back. They had heaved me in, causing bruising to my shins. I felt their hands all over me, tugging at the hood, pulling it down over my shoulders because it was big, and I am small. They tucked as much of me as they could inside what was now a sack. The coarse hessian was rough on my skin. It smelt strongly of body odours and spread a sense of doom. As the vehicle raced on, they jostled to hold me down. I was struggling because I’m claustrophobic , and I was as frightened as a caged animal. My lungs were sucking in the chafed fibres that had been loosened as they wrestled with me. With my hands tied behind me there was nothing I could do to save myself.

I imagined the two young officers stony-faced and smug. My last image of them was at the door towering over the old man who had sheltered me for almost a year. They had swaggered then in front of him, amused with the satisfaction of youth lauding it, usurping the precedence of age. They were insolent, yet sheepish with the unnatural nature of the flip. For me it was no different. It was strength over weakness, nature in the raw. They sat either side of me and pressed the muzzles of their guns hard against my thighs.

I had a memory of hoods. Long time ago. Memory of a gallows against a church wall. Not a Christian affair. More a tyranny. I had seen tyranny from the outside, never imagining the inside and how completely a hood smothers you. Like tyranny does.

Why the hood I asked myself, not myself though.

Why a hood, I asked the indifferent universe. What was it I must not see? Their faces? The route? No it was none of these. It was a hood because, once you cannot see the world as you saw it before, you cannot be of it as you were. You are gone inside yourself where the heart beats faster, blood pulsing noisily in your head. And that is absolute fear, fear without defence. Not fright nor flight but pulsating flow of blood through veins, viscous and life-driven. There is no fight or flight. There is freeze in a sweat.

Sweat poured down my face so profusely I could not tell its moisture apart from my tears. The world that passed along outside me was muffled. Fibres filled my nostrils, I breathed too fast with my mouth open and at some point I must have gone unconscious.

I found the two youths anxiously staring at me. I was lying on the road, the hood removed. They seemed sorry. They fussed about me and offered water. They smiled when I drank. They wiped my face. They untied my hands. They were no longer the brutes I had seen in them. They seemed relieved.

I wondered now what their purpose could be. I made the rest of the journey without the hood. But I registered nothing of the landscape we passed through. I did not care to see, to feel, to forgive, to remember. I could only be. For who was this person who was me? What right had I to be here? What purpose did I serve? What did it mean if they had rescued me after first breaking me out of the quiet oasis I had thought I could be a part of?

How painful now to think of Ramzi’s wife with her newborn son. To think of their kindness to me. The risk they had taken and the danger they could now be in. Only now – as my distance from them stretched not as a road but as a line of time that after so much lengthening must thin to a thread of spider gossamer and snap – only now did I understand the risk they had taken to shelter me. I could not bear to think about what could happen to them, neither could I let go of the thread .

Notebook One continued….

Chapter Two

Between stone and sand

Alert to the immediate threat to his family, Karim turned his back on the field where his flock lay, still and bloodied. Desperate to find his wife, son and infant child, he rushed to find a place to run to. He remembered the ruins of an Ottoman fort, not far from the oasis. It was a ruin now, and served no purpose other than shelter. He had often driven his flock over its gravel rubble to graze on the few patches of grass that grew there. At times, he had lain prone in its stony skeleton to shelter from the wind. His sheep would find comfort huddled together and pressed close to the ground. Other times, he had crouched up against a wall to hide from the sun, and felt the hardness of stone against his back, its unforgiving nature so unlike the fluid talc of sand that slipped through his fingers and could form a soft mattress. At times of bad weather, with desert floor on the move and the gibli blowing grit and dust, he had stayed the whole night with his flock. Once, he had sheltered there under a cloud of locusts that had darkened the sky. Their flight had taken hours to pass over.

At the fort, they discovered they were not alone in their distress. Many others had found the place before them. They too were dispossessed of land and everything they owned. They were startled and confused. Though made destitute, they were not yet aware of their changed status; not ready to understand that they were now subject to the yoke of a new colonial power, whose coming had long been rumoured though never imagined – never imagined because which of them could have envisaged the scene they were now part of, their land trampled by an army of mechanical beasts and armed men whose language was strange and whose origins they could not guess at. They had been thrown together in disarray and found themeselves in the ruins of a place long-time passed and thought of only as a timely reminder of man’s witless arrogance.

The infant Amna cried as other infants did. Their small bodies were resonating with the distress of the trauma, so many mothers rocking their children to sleep hoping to counter fear with their fortitude, and yet weeping. Karim was appalled by the wailing, Amna’s cries multiplied so many times over in the enclosed space of the bounds of walls that bounced the wailing back. He had never before sensed human frailty so piercingly real. Not even in the worst of storms. The elderly were either lost in stony silence or they were cursing. They sat unconsoled and unconsolable. They sat in the dark, huddled like sheep. The cries, the soothing, the weeping, the anger – all dissonant emotions too absurd in their mix to make sense of, except as a mangled nexus of fear of the unknown. Karim felt the hurt so deeply entrenched in his own flesh and bone that he knew he would never forget the violence and injury of it.

It took some little time for the tribes to accept what had happened to them. But not to come to terms with it. That did not seem possible. It took more time to know that in and of itself the devastation was a sign of their reduced status as a subjugated people. They trusted that this could only be temporary, that Allah in his mercy would return them to their true destiny as a people free to roam.

Karim, and others like him, had been alarmed by the spectacle of their grim demise so quickly wrought on them, their traditions so easily blown apart, seemingly fragile like a fabric uncouthly ripped from the face of a bride. And then to have been deflowered of their will to go free with such gratuitous and imponderable violence was unthinkable. He had expected a swift reaction. After all, in the face of an external threat, it was custom for the tribes and clans to come together, even to put aside any feuds outstanding between them.

Perhaps their reaction was muted now because there was fear of the possible greater calamity of mass starvation. More obviously, any kind of resistance was stalled by the lack of arms.And so the tribes had seemed to fall apart, despite their craving for the return of their animals and land, for what they considered to be inviolate to them and impossible to be separate or separated from. They were like moss is to the rock, the lizard to sand or the eagle to the sky.

Karim was the first to speak out, arguing they should seek an indemnity against further atrocity. He dared not speak of other fears, fears for their own slaughter, or the theft of their women and children. This was understood like a shiver down the spine. He was angry beyond constraining anger. He could not bear the thought that he would never again find a place for his wife and child, or a tract of land he might call his own. Shepherding had been his only trade. It had been his diligence and pride that had increased his flock, and won him the reward that was his bride. His voice rang out in the wrangling of argument, raw and shrill, though his nature before had always been measured and gentle.

A novel about different geographies, identity, belonging and alienation. We travel in wild places, wilderness of the mind, nostalgia and loss of memory or experience misremembered. This is one woman’s quest for her lost children and lost places. In the journey, psychological and physical, new realities present themselves as new insights that challenge her perception of herself and of others.

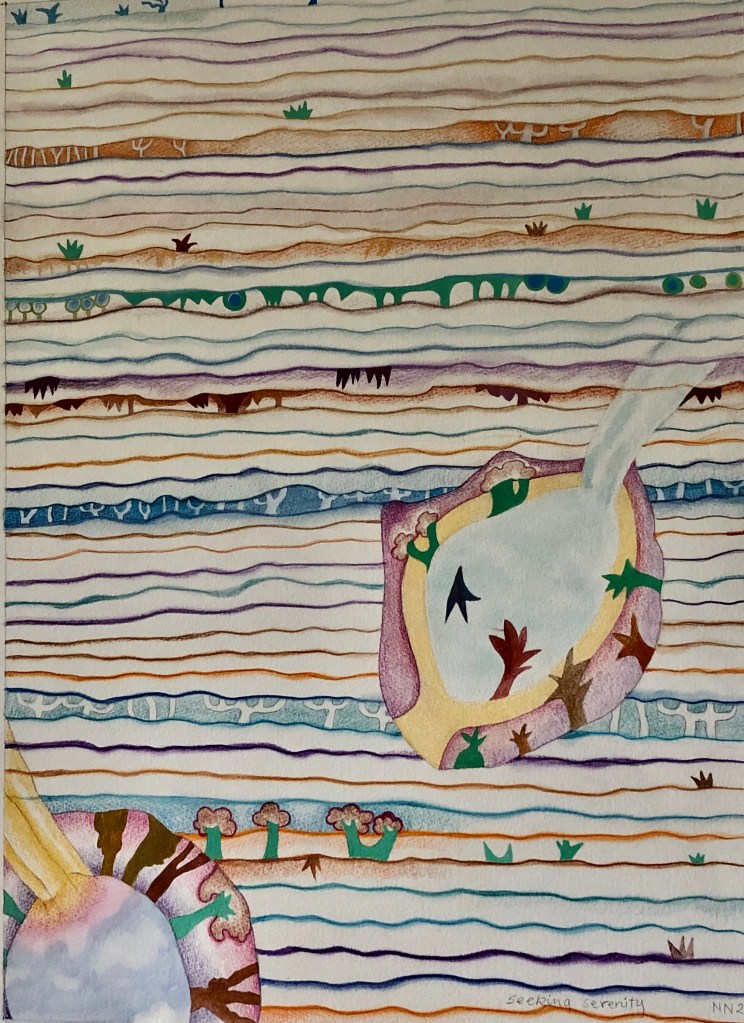

The third novel of a Libyan Trilogy. Presented and serialised in episodes which I call Notebooks. This is the opening of ‘Euhesperides Notebook One’.The image below is of oases in a desert. It may become the cover image for the printed book.

A novel about gardens and wildernesses in the real world and in the mind, physical and psychological. The story is a quest for things lost – memory, children and sense of place. The novel travels across different geographies where identity and a sense of belonging are challenged.

Please feel free to comment.

Opening pages of Chapter One ‘Stock Still’

Chapter One

Stock still

The panicked ewes were bleating for their lambs. They were corralled in a fenced-off quarter of the military barracks. Carabinieri untrained in the business of slaughtering sheep were wielding their combat knives with ferocious intent. The young bedouin watching covered his eyes and wept.

At the order of Benito Mussolini, ruler of the new Roman Empire, Italian ground forces were pushing south from Tripoli. They were reaching the oasis of Ain Zara. As they ranged like scavengers across the Jeffara Plain, they seized the livestock of the bedouin herders who pastured their animals there, doing so according to their ancestral rights. These ancient rights had long been respected under the hegemony of the Ottoman Empire in return for taxes paid; but, with that hegemony now yielded to the jurisdiction of an Italian state ambitious for empire, indigenous rights were disregarded and dishonoured. Bedouin rights were being expunged by a rapacious lust for territory.

The assault had been sudden, on a scale the bedouin could not have prepared for. Being nomads in a desert, they had no equivalent means of defence against a modern military machine. Bewildered and struck by terror, they were helpless and in awe. They watched the brutal theft of their livestock seemingly with little effective retaliation. Donkeys, mules, horses and camels, wild or domesticated, were drafted as carriers of ordnance for the invading troops deployed for the purpose of ‘penetrating’ Libya, taking her by force. By means of stealth and power, the trajectories of empire were reaching south towards Fezzan, expecting to do so peacefully, ‘peacefully’ implying expected surrender.

Karim, whose name means ‘generous’, had been guarding his modest flock from wild dogs. It was early in the night when the Italian Savari had comeriding into the pasture. The thunder of their horse’s hooves had heralded their arrival droning like an afreet. Wilder and more cunning than any pack of wild dogs, they had routed and kettled his scattered sheep into their malevolent fold and driven them away. Shaken and disbelieving of what he had seen with his own eyes, Karim had followed the bandits at a safe distance witnessing the droving of his flock to the military barracks, where, in the chaos of many commingled herds, the lambs were parted from their panicked mothers, and slaughtered en masse. On seeing his sheep suffer this ungodly butchering, he had stood stock still. Still in his shivering skin, but trembling in the sinews that held him taut, while his mind was arrested in dread. He was struck immobile like the stump of a felled tree.

Tell me what you think

by Dr. Bob Donaldson

on reading her debut novel Chameleon in My Garden

BD: Your writing seems to get stronger as the novel progresses? Would you agree?

NN: My first drafts did evolve a lot, that is true. I gained new insights as the writing progressed. Essentially, I wanted to understand what I had been through, but to do so without bitterness; though there was always anger mixed with sadness. There were many varied influences over the many years of drafting and redrafting. It was a long and probing process of discovery, that took more than 30 years. I suppose my writing skills were extended with the new discoveries, factual and psychological, that surfaced.

When a single novel takes so much time to incubate, its creation is transforming. I had time to hone my comprehension of the dystopian world it was set in. Sometimes, I practised by having conversations with an imaginary Colonel Gaddafi, while I washed the dishes. I tried to reason with him. I tried changing ‘voice’ to mirror the contradictory perspectives that made up the complex whole of his psyche.

Then, success in freeing my husband from political detention brought about another twist. It was not safe to return to Libya and join him after my exposure in the campaign. I saw how much danger the fictional Sally would have been in, with her husband still not free. This suggested a new trajectory towards an ending I had not envisaged at the start. I imagine the complexity matured me as a writer.

BD: Are the characters real people or are they based on real people whom you knew?

NN: I selected just a few people whom I knew, in order to meet the scope of the novel. I blended some into a single character. Fathia was real and wholly herself, unchanged in her humanity throughout. There were no characters from real life whom I knew to be openly opposed to the regime, apart from Saad. Everyone was submissive, subdued and restrained, unless they were favoured and operated as informers. There were many who were possibly clandestine critics. I could not have known who they were, so I created them as the story demanded. Hassan was one of these, a character fashioned with some qualities borrowed from a real person and some partly imagined. The secret police were everywhere, very real and generally obvious, as were the fortune-tellers.

BD: Who is Sally? Is she you?

NN: Yes, I suppose she is a fictionalised me. I had difficulty choosing a name for her or giving her any justified purpose in the context of Benghazi. She was alien, a sort of misfit who wanted to belong. I could have adopted a Libyan name for Sally but it would have confused her identity for the reader. At first, Sally was central to the plot. Then, at other times, I wanted to erase her completely. But the novel wouldn’t have worked without her. Sally existed because I was there and experienced the trauma from the inside, not as an expat outsider. So she remained as a permanent fixture, toned down, disempowered and possibly seeming too passive as a result. I am glad she stayed. She creates the tension. However, she remains a conundrum for me.

BD: Why was Hassan in so much trouble? He didn’t seem to do much that was openly rebellious.

NN: Well, remember there were informers in the family and you could never know how far their influence stretched. There was suspicion. There was reasonable paranoia. Hassan knew he was under surveillance. Even so, he was reckless and did dangerous things like fishing along the coast where there was smuggling in the coves. He was inconsistent, usually restrained by fear and outwardly cautious, but also impulsive. He took risks. He protected Sally, in his own distinctive way. He jeopardised the safety of the family.

Hassan carries the main theme of trauma, the challenge of surviving with integrity in the repressive conditions of an authoritarian state. He needed stamina, and to be constantly alert to the danger he was in. He knew there was a surveillance network but he was too disengaged to detect the intelligence links.

BD: What is the function of the chameleon in the novel ? Is it an avatar?

NN: Oh, well spotted. ‘Avatar’ is a good word for it. ’Chameleon’ translates in Arabic to a meaning linked to ‘war’, a semantic link I didn’t make at first. But there was something about chameleons that intrigued me. They belonged in the story. It is a hybrid kind of avatar, because it stood for many things. It symbolised both danger and the search for safety – for itself and for others. It stood in for the intelligence police because it could hide and yet be seen in plain sight, if you knew where to look – now you see them, now you don’t, sort of thing. Even the chameleon’s long tongue was akin to the long reach of the antennae, as the intelligence police were termed. They could reach and threaten you in a number of ways, by radar or telephone tapping, and kerb-crawling. The chameleon was a reminder that no one was immune from surveillance. The chameleon was both a blight and a blighted thing hiding in a garden that was meant to be a safe haven.

The Bosnian war influenced my writing. I remember the words of a Bosnian woman telling how her neighbours, having been their guests at weddings and other festivals, suddenly came over the hedge to kill her family. One of the words for ‘garden’ in Arabic means a place surrounded for its protection. So it had to be Chameleon in My Garden.

And so, I guess, the chameleon is an avatar. Quite a wonderful creature, I think, the way its eyes swivel round to see everything. An alert, apprehensive being thriving in an uncertain world. Also a distraction for the children, as was the feral cat. Maybe the cat is an avatar too. Perhaps she provided the prospect of survival on the fringes. I suppose that was where Sally was.

15/04/21

Wild

the shock of you

bright yellow-collared snake of you

slipping into my view

green of grass and shake

of writhing coils of you

a quick meandering you take

to somewhere blue and new

past the greening make of you

you take the moly river view

where water voles slake

their thirst from river’s dew and you

you skip and slide in fake

dance of fright that drew

flight with quickened loops of you

for a grassy camouflage of hue

for you are wild

it is the pace of your slithering

the race that caught my sight of wild

bright-eyed I thought you were

in glaring yellow eye dissembling

but later learned t’was collar born of wild

to scare the shadow looming there

that frighted and set you undulating

on a track for swift escape to the wild

in panic mode of biding where

the disguise of grass enfolding

shields you and leaves you in the wild

to shiver in your scaly coil there

not knowing that honoured and admiring

I was pleased our paths had crossed in the wild

if only for a moment’s flash there

because you are wild

Tell me what you think

Excerpt from novel Transformed: The Escaped Graphic Child.

There she was at the centre of everything. The centre of everything was a risky place to be for a newcomer. She was teetering on a pivot, like an unpracticed acrobat on a moving trapeze. The world was a great dirndl skirt cavorting In the up-draught of the wind, blowing her this way and that. It rolled away and rolled back, setting her swinging with each return, to be dazzled by a ball of fire.

the hush between pauses

falls away into a mist

of things unsaid

it is an opaqueness

a barrier between the thought

and the word we did not dare to hear

a snowfall of whispers drops into absence

and disperses its blank muteness

in melting sheets of confetti

the unsaid rides like a phantom

bleached under the cold sun

a loosened avalanche of nothing said

with the vanishing wind it is gone

a dream is closed over by heavy lids

an image is consigned to the bin

did we say nothing?

did we never know?

were we so very mute?

.

.

thoughts from the ceramics workshop

the first day of spring eludes us

while drab November malingers

at the workshop window

someone is back from the ski slopes

someone else is off to Berlin and her blog

another is missing from his station

with pewter splashes like a garland

her alabaster head is festooned

and waltzed aloft to the kiln shelf

the smell of wood friction

and meths with shellac mingle

carborundum grinds

the grecian urn deep veined

with fern relief is glazed with wood ash

on chartreuse underglaze

a porcelain seed, Fabergé egg

with seams standing proud

dries in the warming cupboard

your back arched in focussed labour

palm buttressing the clay on the wheel

slurry garnered and returned to reclaim

rose-stuccoed jug of crank slowly drying

coiled vessel with inside opened out

egg-shell blue-rimmed flutedmugs

transparent matt is stirred

a beech leaf is incised in wax

with fine scraffito tool on bisque

a blue-green bust emerges from its cast

the plaster crack ridged across her face

will wear to file pad and wet and dry

shellac filigree for foliage dries on the bat

resist against a water weathering

bathed to translucent thin

paper porcelain petals wait for glass fusion

poppies nod in memory of absent George

Gujarati heads turn in rainbow saris

a lost citadel grows in my head the while

vectors of bird flight cross the boundaries

freeing memories once trapped in walls

it’s snowing somewhere in the north

.

.

Part One: Drought

Cyrene’s slopes are draped

with marble pillars

fallen columns cross the paths

and grass grows free of traffic

a tiled bath drained of water

flashes blue with lapis lazuli

before the ruined base

of the temple to Artemis

fleecy seed heads float

among the long shadows

of Corinthian pillars

white and ghost-like

the cadence of a horn

sounds the evening fall

its trembling prayer

washing down the valley

sighing in the wind

to halt the suffocation

its ululating tongue sings

for the fissured land

Beyond the amphitheatre

a camel lies in coma

poisoned by a silver leaf whose

yellow flower withered after spring

the old lore of sacrifice

washes through her dream;

red and brutal sacrificial blood

floods and rages there

she must sleep on

to death’s last ambush,

dreaming of the coming winter

and winter’s rain

Part Two: Nightmare

Her shortening breath flounders

lodged in inflamed lungs

and the shepherd’s horn is still

At nightfall, the camel draws

away from the struggle

straining to the tread of

a gazelle halting at the glade’s edge

turning to the sea

with the desert at its hind quarters

It scents the brine and bridles

pulled by the tug of thirst

and bleats:

I have come from where nothing grows

along the tracks of dry stream beds

that wave their ribbons of lost hope

fleeing to a salty sea

On cracked earth forking this way and that

a crazed path takes me to a hillside

where a man is bound to a petrified tree

naked on a hillside.

Dogs growl and snarl around him

snatching at his kneecaps.

Through the night he groans

fading into dawn’s mist.

His pitted flesh leans there

into sand-gritted wind.

He seeks my touch

but I must run.

Leaping on

drawing breath

from the blue edge

of a crescent headland

the gazelle quenches its thirst

in a salt swell

with throat salt-encrusted

blood dried and curdled

The camel has a vision

and shudders in her shelter

under the canopy

of green oleander

a fennec fox glides

over the stone wall

and scents the body

lying in the dust

Sifting through the dust

it finds the camel’s eye

staring under drowsing lashes.

The camel stirs and

thinks the pointed face

is the maddened prisoner

his face scored with tears

that drip a soundless protest:

I answer ’no’

for that is all I have

that is still mine.

I spoke of love

and hate received

from men who feared Reason

No is what I am

No is the action I carry

No is the people you would have me name

No is the plot you say was mine

No is the death you have prepared for me

No is the succumbing to that end.

Part Three: Rain at last

Large drops pressed the dust

plunged the riven cracks

and bounced on iron furrows.

Rain pummelled the earth

into putty softness

carving a corkscrew channel

in a drowning hill.

Red water turned and turned

its watery blades pounding

off-loading loam into the bay.

On the rushing hillside

lay the camel waking;

the flood dividing at her shelter

she heard its roar.

In the orchard of pomegranate

in a rain vast valley

the almond tree cracked.

Rain chiseled a path

with measured pouring

along split boughs

and peeling bark

into red mud earth.

Torrents rumbled the fall

of a sliding surface

that moved into the sea.

Unhinged in bleached memory

the camel waded

through white spaces

of whitening fear.

Witness, camel, how painful

the dying of the prisoner now

in the tumultuous cries

of day’s arrival

how painful the passing away

in the sensational morning

that follows night.

Part Four: Aftermath

A father kneels in new grass

on flowers petal-crushed

and whispers his despair

in supplication over each shoulder.

A mother turns to the tall cypress

in her grief-frozen distance

she reaches for the sky

and birds in flight

A wife gathers her children

consoling and holding them

and their shock stands still

at the centre of embrace.

.

.

something in the mind tells me I am overheating

singed neurons frazzle in the brain’s map

the pillow is a lump of rock

the mattress a tarmac road

my blanket is a collage of the cast skins of cicadas

my limbs reach out for air

my lungs expand for want of oxygen

my eyes bulge under prickling lashes and

I press down into the sackcloth vacuum of evasive sleep

the soaring fahrenheit of day barely tumbles in the night

heat accumulates overcasting my breath like clouds of fog

suffocating my thoughts of dreaming light

with would-be somersaults of washed-out energy

nouns are conjugated and verbs disagree with their subjects

facts are slashed across with half-forgotten memories of what was known

somewhere along the way

what was once so sure melts like skewered marshmallow in a flame

the race of time slows and sinks into the raucous din

of insect abdomens vibrating in an insect rally for a mate

the cicadas sing all day and night

competing with some imagined monster rival

the motors of air conditioning buried deep in concrete fabric –

drown conversation with their orchestral performance

the insect horde tunes its forte to crescendo pitch

in overlapping waves of night thermals

from their lofty perches they drill with incessant strokes into the tremors of night heat

while a lone cricket bells its piercing strumming to the heat haze

stoking up its symphony to mercury peaking in a glass

stranded in the still air it strikes a strident note

a monotone of something trapped

like the moth struggling in the heating duct its wings bruised in its panic

the panic in me

as the train’s siren wails its hooting warning across the prairie reminiscent of Western movies and

as the gargantuan refuse truck booms its heavy sweep of melting tar its tyres squealing in the traction

the pillow softens

the mattress relents and

the horizontal receives me

my limbs are abandoned stranded apart north west east and south

my brain is carded into felt

Then in a sudden the moth breaks free from its furnaced holding and

fills the night air with its dark fluttering

Before the day swells up like dough sweating in an oven

the piano tinkles its amazing grace with lilting cadence right to the final coda

then as morning proves itself again

its strains challenge the cicada to a contest

belting out its hymnal to the chorus of morning has broken

the cicadas strum louder still so that

the beat of their tumultuous concert

is like the rhythmic throb of the first awakening

when primal earth first poured forth its molten mass

.

a racket in the tall cypress

splits the sweep of its upper limbs

a ragged etching of graffiti

like a crown of thorns

a squall of crows squabbles

for a lodging on the bough

feathers ruffled by a blast of wind

flutter in a ragging breeze

the chain saw and the digger

leave their tracks of scarred earth

fences felled and soil turned over

by an intruding harvest storm

the path below is strewn

with a shake of sweet chestnut

blown along in rolls like wooly baubles

prickly green burst-open chestnut red

the vines stretched low with grapes

the ripening a ‘johnny come lately’

of Indian summer set a-trembling

at the shock of the bird scarer

the chestnut sprawl beneath my tread

lies amiss beneath the tall spruce

like cuckoo debris driven to the wrong place

by an indifferent tenant wind

I step over the hoard gingerly

in orange pumps reminder

of the summer almost gone

ablaze in the sodden grass

dragonflies on the bridge

prance in their final hours

the fishermen count the days

before the storm of autumn

and summer soon will be all gone

.

conversation with a fisherman:

the deer morph from leafy screens

shy, reticent and canny

to the changed air

the mole seeks its chance to forage

pragmatic swimmer carried

by strokes meant for digging earth

a rabbit flees from ferrets

confused enough to tarry

at the lake’s edge

before the necessary plunge

and all the while

leather carps indulge

slow, sluggish and unhurried

by the fishermen

all is hidden from the busy walker

the strolling mother and her buggy

the lovers wrapped in dreamy vistas

the couple with the wheelchair

they wow the swooping swans

they mew the gosling geese

survey the vines’ late ripening

and spy the parrot in its showy flight

and all the while in quiet diligence

the gardener trims and prunes and tidies

the steward notes the signs of growing stock

the groundsman checks for wear and tear

the fisherman plays hide and seek with fish

so that “when you good folk have all gone home”

the deer can morph from leafy screens

and retrieve the landscape as their own

“when you good folk have all gone home”

.

Tell me what you think